"We are sincerely thankful that the good name of our friends, Cadbury Brothers, has been vindicated at the Birmingham Assizes after a trial extending throughout seven days. To Friends to whom the family are known, either personally or by reputation, the charges of dishonour and hypocrisy brought against them in regard to their dealings respecting cocoa from San Thomé and Principe were incredible."

The editorial continued by praising the judge, who pretty well directed the jury to find for the Cadburys and by sympathising with William A Cadbury for the ordeal of being cross-examined in open court.

The case was a libel action brought by Cadbury's against a newspaper which accused the company of hypocrisy in continuing to buy cocoa beans from Sao Tomé and Principe long after it was evident to the company, and to any dispassionate observer, that the beans were grown and harvested under what was, in practice, a brutal form of chattel slavery masquerading as indentured labour. The Cadbury family, in collaboration with the Rowntrees and the Frys, were not only slow to act; they had also done their best to conceal the facts while searching for an alternative source of cocoa beans. In 1901, William A Cadbury wrote to fellow Quaker and anti-slavery campaigner Joseph Sturge acknowledging that one "looks at these matters in a different light when it affects one's own interests".

It took the Quaker chocolate manufacturers several years to decide on action. The 1904-5 reports of Henry W Nevinson, who had approached Cadbury with an offer of assistance, might have spurred them into action but Nevinson was a difficult character - a radical, far from quiet who didn't speak Portuguese, the language of the slave-plantation owners. It didn't occur to Cadbury that it might be helpful for anyone to learn the languages spoken by the enslaved families. The Quakers acted very slowly indeed and in accordance with their own interests.

Meanwhile enslaved people died. In 1902 William A Cadbury had heard from a missionary that the life expectancy of a newly-enslaved worker on the plantations was three and half to four years. One model plantation had a lower annual death rate of between 10 and 12% which it ascribed to anaemia caused by unhappiness. The death rate for children was around 25% per year. As information reached Britain and by 1907 William A Cadbury reported, when he attended a Quaker gathering in London, that many considered "we were acting hypocritically, although nobody quite said that word." It was in the following year that the Standard published an editorial condemning the "strange tranquillity" with which the "virtuous" owners of the chocolate companies had received reports of slavery - and that was the editorial which Cadbury, rather than demanding a retraction, chose to make the grounds of his case for libel.

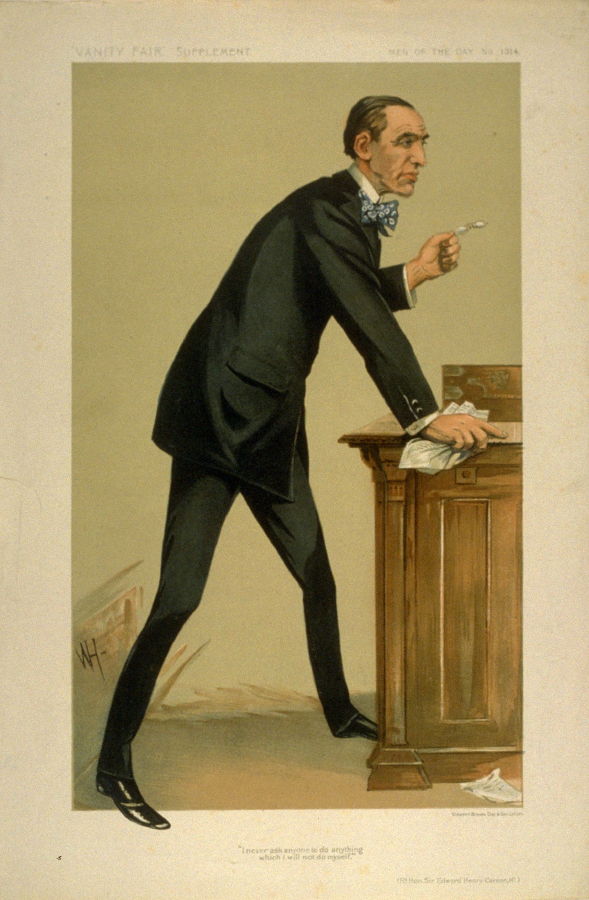

The case was heard in Birmingham and the jury followed the judge's direction in deciding that Cadburys had been libelled. They then had to assess what damages to award Cadburys. The jury had heard the case and learned all about the brutal practices of enslavement and the high death-rate. They had watched William A Cadbury as he was cross-examined by Carson. The judge suggested that substantial damages should be paid to Cadburys but the jury did not agree. They awarded the lowest damages possible - a single farthing (a quarter of an old penny).

The editorial in The Friend doesn't mention the derisory damages. Instead it quotes the judge and insists that Quakers as a whole must support the Cadburys because they are known personally by some and have a good reputation in the Society.

But this isn't how we should decide matters. It doesn't matter that we might see and understand the difficulty that the Cadburys and the Rowntrees and the Frys faced in sourcing good quality cocoa beans. If we always take the side of those we know and respect - as though they could never make a mistake let alone do something wrong - we will quickly find that we are doing our best not to hear or even to silence other voices. The voices of the enslaved people on Sao Tomé and Principe deserved to be heard. They deserved to be acted upon. Enslaved workers in Sao Tomé sang a chantey: "In Sao Tomé there's a door for entrance, but none for getting out."

For eight years after first hearing of slavery on the islands of Sao Tomé and Principe, the Quaker chocolate firms continued to buy cocoa beans from the plantations there. They meant well. Towards the end of his cross-examination of William A Cadbury, Edward Carson asked, "Have you formed any estimate of the number of slaves who lost their lives in preparing your cocoa during those eight years?" Cadbury couldn't answer. A low estimate would suggest 4,000-5,000. The number may well have been much higher.

_p11_STATUE_OF_WILLIAM_PENN.jpg?download)